My fascination with Copperhill dates back to late 2009, when I was just a junior in college. As an undergrad in the landscape architecture program at UGA, I would occasionally join my classmates on field-learning opportunities, as a way of seeing firsthand how we as landscape architects would shape the natural world around us - for better or worse. That fall, one of my professors had us studying the tenets of land management - utilizing natural resources such as timber or wildlife in a sustainable way that doesn't degrade the quality of the harvested ecosystems. This is a complicated field and, at many universities, a degree in and of itself. As a landscape architect, though, this is just one of many environmentally-related subheadings with which we need to be familiar. As a way of driving home the importance of the subject, my professor decided to expose us to an example of what can happen when these principles are ignored to disastrous effect. We would be heading to a town called Copperhill, Tennessee.

You may recall from my previous post how virtually all of the vegetation around this area had been decimated as the result of the one-two punch of clear cutting and sulfuric acid rain. After the mine and reclamation plant were decommissioned in the late 1980s, the area slowly started to transform into something that even lifelong residents had never seen around those parts - a forest.

Restoration efforts to heal the Copper Basin came in many forms, including aerial reforestation, bioremediation and water-treatment plants. As part of our class visit, a local biologist showed us around some areas on the mine property where remediation was proving successful. I remember at one point, as we stood next to a constructed wetland used to filter heavy metals from stormwater runoff, I let my mind wander away from the lesson - off in the distance, over the tops of the young pine trees, I could see a collection of aging buildings that managed to survive the dismantling of the adjacent smelting plant.

(Source: The author's own)

I wondered what those buildings might have been used for and why they had been spared. Though I would never get a chance to see the infamous plant itself, maybe one day I could come back here and...pay a little visit to those buildings up on the hill. Yep, my curiosity was officially piqued. As the class shuffled off to the next reclamation project, our feet stirred up a lazy cloud of ochre dust that swirled and danced up beyond the pines, masking the buildings from view.

This post is going to be the first of many to touch on a subject very near and dear to my heart that also kind of freaks people out - trespassing. For those who know me, this should come as no surprise; "urban exploring" (as the kids call it) has been a passion/vice of mine for just about my entire life. What's the difference between that and trespassing, you may ask? Well, you could say that all urban exploring is trespassing but not all trespassing is urban exploring. We focus on the places that society has forgotten. Urban exploring appeals to people for a whole host of reasons - photographers, amateur historians, thrill-seekers, architecture buffs, you name it. But we are also respectful (well, most of us). We understand that we're visitors to someone else's property and we alone are responsible for our actions, no matter what happens. We leave nothing but footprints and take nothing but pictures. We know the risks and we accept the inherent danger (both corporeal and legal) that comes from pursuing this unconventional hobby.

The trade-off, for me at least, is well worth those risks. Have you ever watched a sunset from the roof of an unfinished nuclear power plant? Or felt the vibrations of a freight train while clinging to a catwalk eighty feet over the middle of the Mississippi River at night? Have you ever heard the silence that comes from being enclosed in a body freezer, in the morgue of an abandoned sanitarium?

I have.

It's addicting. Folks either love it or hate it and I fall unabashedly into the category of the former. Admittedly though, when I come across a potential hit for an urbex trip, I sometimes get a little obsessed; so, you can imagine how gratifying it was to finally come back to Copperhill all these years later to cross the reclamation plant complex off my list.

Two days after our railroad excursion through the mountains, I once again rolled into the outskirts of Copperhill, just a stone's throw from the old slag dump. Here's what I was up against:

Points of interest around the site.

(Source: Google)

After stashing my truck off-site where it wouldn't be discovered, I hoisted a bag full of gear over my shoulder and started the half-mile hike toward the plant complex. I approached the grounds from the north, where the kudzu fields weren't quite as thick. The tangle of vines quickly gave way to a young pine forest as I started making my way up a hill forming the northwestern boundary of the site. As I crested the hill, exposed cliffs of burnt sienna rose before me. An open pit mine maybe?

(Source: The author's own)

Crouching atop the hill so as not to be seen, I took a moment to appreciate just how quickly nature had reclaimed this place. There was a time not too long ago when this was a moonscape - not a green thing in sight.

As I slipped and slid down the dusty embankment toward the gravel road below, strange details of the landscape started coming into view. Spherical minerals like BBs eroding out of the earth, creek water the color of bile and rusted industrial remnants poking from the ground like headstones.

Source: The author's own.

Brambles and broomsedge crunched underfoot as I bushwhacked my way across the muddy floodplain and up the opposite hill to my first target - the train depot. For the record, I usually do my homework both before and after an urbex trip so that I can at least make an educated guess about what I'm seeing. Sometimes, though, that can be difficult when dealing with an unfamiliar industry. I am not a miner, chemical engineer or geologist and I don't know any miners, chemical engineers or geologists (if anyone reading this wants to chime in with thoughts or guesses about some of this stuff, feel free to leave a comment at the bottom!).

Through context clues including a triple set of rail tracks, I feel confident that this first building served as a maintenance shed for tank cars (a nifty poster on the wall showing the anatomy of a tank car was a dead giveaway).

(Source: The author's own)

Once inside the shed, I tiptoed around clumps of rotting wood, glass shards and crumbling asphalt shingles from a partial roof collapse. To my immediate left, I noticed an open door to what was most likely the shop foreman's office. Peering inside, the beam of my headlamp illuminated something rarely seen in an abandonment. Aside from a thick crust of red dust and cobwebs, the office looked presumably just as it had when the plant was active. Coats still hanging on their hooks, inboxes still stacked with cracked, yellowed paper and a refrigerator full of leftovers from three decades ago.

Typically, desirable urbex targets like this one attract a lot of traffic from explorers, so artifacts are moved in order to set up better photos or they just go missing entirely. Vandalism is also a big problem and one of my personal pet peeves - as a history buff, it's hard to imagine life as a Copperhill maintenance tech while surrounded by colorfully spray-painted dicks. But this place was largely intact. During the late 80s, as the plant management started to downsize its labor force, the local union organized a strike as a last ditch effort to preserve their jobs (spoiler alert: it didn't work).

As I stood there in the office, trying not to stir up carcinogenic dust from the peeling linoleum floor, I could imagine the foreman across the table from me, having a heated argument over the phone. With one final swear, he slams the phone down where it bounces off the receiver and falls to the floor. Red-faced and furious, he grabs his coat and storms out of the room toward the picket lines. He would never step foot in that office again and, thirty years later, the phone still rests haphazardly on the floor.

Maybe it didn't go down like that but isn't it fun to imagine? Now you see why graffiti wieners are such a buzzkill.

(Source: The author's own)

Stepping back out into the sunshine, I followed the remnants of a railroad spur toward the next set of buildings, hopping from one cross tie to the next (workers had long ago ripped up the steel tracks for scrap). These two remaining buildings served as some sort of fabrication facility, though for what product(s) I could only imagine. Massive spools of wire and acid storage vats suggested different uses, though it's possible the buildings had been converted to storage shortly before being abandoned - we run into that a lot. Curiously, a portion of one building had been demolished but the job was never completed - slabs of concrete dangled from the roof on strands of rebar like pilling on a wool sweater.

(Source: The author's own)

Starting at ground level, I cased each floor, stepping carefully to avoid broken glass and gaping holes where pipes had once snaked through the structure. After climbing four narrow flights of stairs, I reached the roof. Like the final boss of a kung-fu movie, I kicked open the rusted rooftop door and sent forth a majestic cloud of pigeons as I stepped out into the cool mountain air (but only after screaming in the dark stairwell as a dozen startled pigeons swooped down at once and scared the bejesus out of me).

(Source: The author's own)

From the roof, I could see the sun sinking lower in the sky, meaning that I needed to get a move on if I wanted to see more of the site; common sense told me that being here after dark would be unwise. Since the main building complex near the slag dump was still semi-active (including a part-time security guard), I decided to stick to the back roads and check out another large building on the east side of the grounds - what appeared, at first glance, to be administrative offices.

(Source: The author's own)

Instead, I discovered something much more intriguing. In the countless abandonments I've explored over the years, never before had I seen anything like what I was about to find inside.

I had stumbled into the chemical engineering laboratory. The building itself suffered from some serious water damage - mold grew from the damp carpet and the air was thick with the earthy smell of mildew. Clumps of asbestos littered the floor from where fireproofing panels had dropping from the ceiling. Because of the bad air, I dug my respirator out of my bag and strapped it across my face. Two P95 particulate filters - one on each cheek - would provide me with a good protective barrier against any harmful airborne particles. Still, I stepped carefully, trying not to kick up any more dust than I had to.

As I pointed the beam of my flashlight into the first lab, had it not been strapped in place by my respirator, my jaw would've dropped.

(Source: The author's own)

There before me sat row after row of pristine glassware - flasks, beakers, pipettes, burettes, you name it. To see that much unbroken glass in an abandoned building is rare enough but many of these containers still had chemicals in them; it was as as if the chemists went on break and just never came back. Sulfuric acid solutions and who knows what else filled the drawers and cabinets. From flask stands covered in at least two decades of rust hung various pieces of glassware, each appearing clean enough to have just come out of the box.

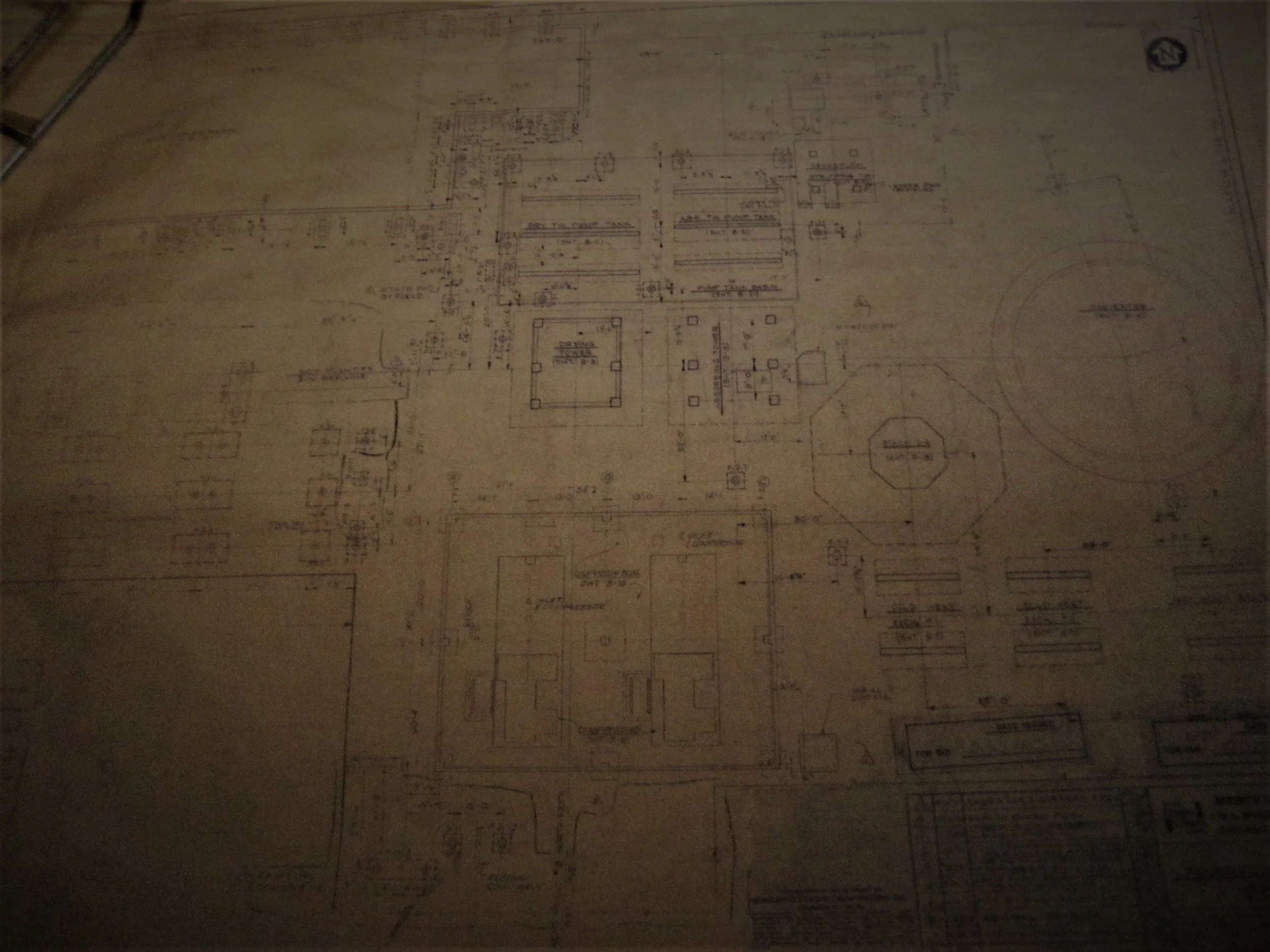

The sound of animals shuffling in the walls echoed throughout the building as I investigated one room after another of intact artifacts, all surrounded by darkness. The labs themselves were located in the center of the building away from any windows, so each room was as black as night. I tell you, the sheer volume of unvaldalized stuff in that building was truly staggering. Even the reading room was fully stocked with schematic prints, regulation manuals and aerial maps of each mine operating in the Copper Basin during its heyday.

(Source: The author's own)

I easily could've spent an entire day rummaging through that one room but my time was quickly running out. As I passed by a dusty window, I could see that I was on the verge of losing my daylight. The trek back to civilization would take me another hour at least, so it was time to get moving.

As I hiked along the dusty gravel roads back to the spot where I'd hidden my truck, I could see pine shadows stretching long across the eroded gullies of the mine spoils. The orange creek water flowing lazily through the valley below me glistened in the warm light of sunset.

(Source: The author's own)

Copperhill truly is an amazing place, both in its history and its recovery. What was once one of the most heavily denuded landscapes in the United States, if not the world, is now in full successional swing - pioneer species like broomsedge and pines are transforming this landscape into something that may very well one day resemble the Copperhill of old - before the copper. Or, at least, before we knew about the copper.

I reached my truck around dusk, pleased to discover that Gabby was sleeping peacefully in the backseat. Having crossed a big item off my bucket list, I pulled out onto the highway with a surging optimism that maybe this road trip idea might work out alright after all.

CWO